Randy Jacobs, M.D. Patient Education

To return to the Patient Education page and read more articles, click here.

Exanthems - Rubella

CHILDHOOD

EXANTHEMS: Rubella

Introduction

Exanthems are a common cause of generalized

rashes in children. They pose a diagnostic challenge to even the most

experienced physician because of the diversity of their clinical presentations.

The morphology distribution, and associated signs and symptoms are sometimes

specific enough for a definitive diagnosis, but, nonspecific clinical findings

often make this impossible. Advances in laboratory techniques (particularly in

viral diseases), new antiviral drugs and vaccines, epidemics of old exanthems, and the recognition of new clinical syndromes

have stimulated renewed interest in exanthems.

Historically, exanthems were numbered in the order in

which they were first differentiated from other exanthems.

Thus, "first" disease was measles (rubeola),

"second" disease was scarlet fever, and "third" disease was

rubella (German measles). The specific disease described as "fourth"

disease, so-called Pilatov-Dukes disease, is no

longer accepted as a distinct clinical entity, with some authors speculating

that it represented staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and others

speculating that it was concurrent infection with both scarlet fever and

rubella. Fifth disease is erythema infectiosum, and

sixth disease is roseola infantum.

Only in the last decade, with the identification of parvovirus B19 as the cause

of erythema infectiosum and human herpesvirus 6 as the cause of roseola infantum,

have the causative agents of the classic exanthems been identified.

Rubella

Rubella

is also known as German Measles or Three-Day

Measles. Rubella is a contagious viral

disease characterized by swelling of Iymph glands and

a rash. A pregnant woman infected with rubella during the early months of

pregnancy may develop an abortion, stillbirth or congenital defects in the

infant.

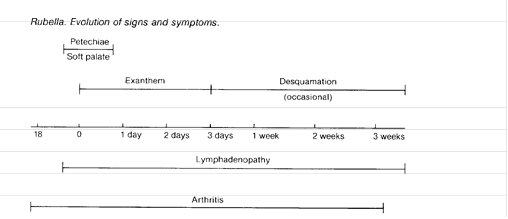

Symptoms

Rubella

has a 14- to 21-day incubation period and a 1- to 5-day preliminary phase in

children. The preliminary phase may be minimal or absent in adolescents and

adults. Tender swelling of the glands in the back of the head, the neck and

behind the ears is characteristic. The typical rash appears days after onset of

these symptoms. The rubella rash is similar to that of measles, but it is

usually less extensive and disappears more quickly. It begins on the face and

neck and quickly spreads to the trunk and the extremities. At the onset of the

eruption, a flush similar to that of scarlet fever may appear, particularly on

the face. The rash usually lasts about three days. It may disappear before this

time, and rarely there is no rash at all. A slight

fever usually occurs with the rash. Other symptoms such as headache, loss of

appetite, sore throat and general malaise, are more common in adults and

teenagers than in children. After-effects of rubella are rare among children,

although there have been cases of joint pain (arthralgia), sleeping sickness

and blood clotting problems. Adult women who contract rubella are often left

with chronic joint pains. Encephalitis is a rare complication that has occurred

during extensive outbreaks of rubella among young adults serving in the armed

services. Transient pain in the testes is also a frequent complaint in adult

males with rubella.

Cause

Rubella

is caused by an RNA virus of uncertain classification (probably a toga-virus),

and is spread by airborne droplet clusters or by close contact with an infected

person. A patient can transmit the disease from 1 week before onset of the rash

until 1 week after it fades. Congenitally infected infants are potentially

infectious for a few months after birth. Rubella is apparently less contagious

than measles, and many persons are not infected during childhood. As a result,

10% to 15% of young adult women are susceptible if they have not been

vaccinated against the disorder. Many cases are misdiagnosed or go unnoticed.

Before the rubella vaccine was developed, epidemics occurred at regular

intervals during the spring. Major epidemics occur at about 6 to 9 year

intervals. Once infected by rubella, immunity appears to be lifelong.

Similar Disorders

Measles,

scarlet fever (scarlatina), secondary syphilis, drug

rashes, erythema infectiosum (fifth disease),

infectious mononucleosis, and echo-, coxsackie- and

adenovirus infections must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Rubella

is clinically differentiated from measles by the milder rash that disappears

faster, and by the absence of the small, irregular, bright red spots (Koplik's spots) on the mucous membranes inside of the

cheeks and on the tongue, a running nose (coryza),

the aversion to light, and a cough. A patient with measles appears more sick, and the illness lasts longer. With even mild

scarlet fever (scarlatina), there are usually more

constitutional symptoms than in rubella, including a severely red, sore throat.

The white blood cell count is elevated in scarlet fever, but is usually normal

in rubella. The rash and swollen Iymph nodes (adenopathy) of rubella can be simulated by secondary

syphilis. However, the Iymph nodes are not tender in

syphilis and the rash appears bronze-like. If there is doubt, a quantitative

serologic test for syphilis can be performed. Infectious mononucleosis may also

cause a rubella-like swelling of Iymph nodes and a

skin rash, but can be differentiated by the initial lack of white blood cells

(leukopenia) followed by an increase in white blood cells (leukocytosis). Many

typical mononuclear cells appear in the blood smear, with appearance of

antibodies to the Epstein-Barr virus. In addition, the sore throat of

infectious mononucleosis is usually prominent, and malaise is greater and lasts

much longer than in rubella. A clinical diagnosis of rubella is subject to

error without laboratory confirmation, especially since many viral rashes

closely mimic rubella. Acute and convalescent serum should be obtained, if

possible, for serologic testing. A 4-fold or greater rise in specific hemagglutination inhibiting antibodies confirms the

diagnosis of rubella.

Therapy

Standard Therapies: Prevention is the most important

therapy. The purpose of rubella immunization programs is to prevent some of the

catastrophes associated with congenital rubella. All children between the ages

of 15 months and puberty should be routinely vaccinated against rubella. Women

of childbearing age whose blood tests negative for rubella hemagglutination inhibiting antibodies should be immunized. Conception should be prevented for

at least 3 months after immunization. Rubella, itself, requires little or no

treatment. Middle ear infection (otitis media), a rare complication, is usually

treated with penicillin or other antibiotic.

|

|