Randy Jacobs, M.D. Patient Education

To return to the Patient Education page and read more articles, click here.

Pemphigus

|

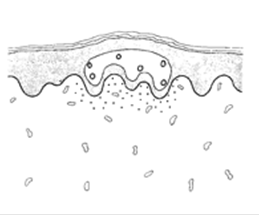

Definition: Pemphigus is an autoimmune skin disorder characterized by blistering of both the skin and mucous membranes. Pemphigus is defined as a group of chronic blistering diseases in which histologically there is acantholysis and blister formation within the epidermis. (Acantholysis is separation of the epidermal cells from one another as a result of loss of intercellular bridges.) Pemphigus vulgaris is the most common form of pemphigus.

Causes, Incidence, and Risk Factors: Pemphigus vulgaris is generally seen in patients in the fourth or fifth decade of life. It is a disease of middle age and only rarely does it affect children. It affects both sexes almost equally, although under 20 there is a predilection for women. Pemphigus involves blistering of the outer (epidermal) layers of the skin and mucous membranes. Pemphigus is an autoimmune disorder where the immune system produces antibodies against specific proteins in the skin and mucous membranes. These antibodies produce a reaction that leads to a separation of epidermal cells (acantholysis) from the anchoring structures of the skin. The exact cause of the development of antibodies against the body's own tissues (autoantibodies) is unknown. A few cases have occurred from reactions to medications, including penicillamine and captopril. Autoantibodies were first described in patients with pemphigus in 1964. Today, pemphigus is thought to be caused by an antigen-antibody reaction, in which circulating immunoglobulins (IgG) are directed against an epidermal substance called the glycocalyx. It is believed that glycocalyx acts as an intercellular "cement" that helps skin cells to stay together. The antibodies bind to the glycocalyx and elicits the release of proteases which are enzymes that alter its "cementing" characteristic. This results in the loss of cell adhesion. Pemphigus has been found to coexist with a number of other disorders that are characterized by immunological disturbances such as lupus erythematosus and myasthenia gravis. There is also evidence that pemphigus may have a genetic basis. More than 95% of people with pemphigus have specific HLA antigens, and thus, certain families are at risk. There is evidence to suggest a definite increased prevalence among Jews and HLA studies in pemphigus patients have demonstrated striking prevalence of the disease in people with certain HLA antigens.

Symptoms: Pemphigus is uncommon. It occurs almost exclusively in middle-aged or older people, of all races and ethnic groups. About one-half of the cases of pemphigus vulgaris begin with blisters in the mouth, followed by skin blisters. The blisters (bullae) are relatively asymptomatic, but the lesions become widespread and complications develop rapidly and may be debilitating or fatal. The lesions of pemphigus vulgaris are flaccid and generally develop on non-inflamed skin. Clear bullae or occasionally pus-filled blister arise. These blisters are readily broken and produce large, weeping, denuded areas of skin. Areas of predilection are the scalp, trunk, pressure points, groin, and axillae. The flaccid blisters demonstrate "Nikolsky's sign", which is pressure on the edge of a blister with a finger or blunt instrument will result in lateral spread of the blister or a shearing of the superficial layers of skin. This sign can also be demonstrated on areas of skin without blisters. It is a helpful diagnostic sign because it is seldom elicited in uninvolved skin in other bullous diseases. Mucous membrane lesions occur commonly in pemphigus vulgaris. In fact, oral lesions may be the presenting feature and may persist for a period of time before blisters occur on nonmucosal skin. These oral ulceration may actually extend anywhere from the lips to the upper part of the stomach. These are painful erosions that can make eating and swallowing difficult. Other mucous membrane regions may be involved - such as the nasal area, larynx, vaginal mucosa, conjunctiva, and even the rectum. The individual pemphigus lesions are tender. With or without therapy, they heal slowly, leaving residual hypo- or hyperpigmentation. True scar formation is unusual.

Prevention: There is no known prevention for pemphigus vulgaris. Skin lesions recurrent or relapsing blisters, flaccid mouth ulcers, or skin ulcers deep may drain, ooze, crust located on the mucous membrane of the mouth located on the scalp, trunk or other skin areas spreading to other skin areas. superficial skin peeling or detaching easily.

Signs and tests: Nikolsky's sign is positive--when the surface of uninvolved skin is rubbed laterally with a cotton swab or finger, the skin separates easily. A skin lesion biopsy shows acantholysis as described above. An examination of the biopsy tissue with immunofluorescence confirms pemphigus. The Tzanck test of a smear from the base of a blister shows acantholysis, as well. Diagnosis of pemphigus is confirmed by routine biopsy specimen and immunofluorescence studies. Histologically, pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by suprabasilar acantholysis; that is, acantholysis occurs with basal cells remaining attached to the basement membrane at the blister floor. The basal cells also lose their attachment to one another so that they stand apart like a "row of tombstones." Also, rounded epidermal cells lying in blister fluid are commonly seen. Direct immunofluorescence shows deposition of IgG in the intercellular space of both involved and uninvolved skin. On indirect immunofluorescence study, most patients with pemphigus vulgaris have a circulating IgG that binds to the intercellular spaces of epithelium. The titers of this antibody reflect disease activity and can be followed as part of patient management.

Treatment: Systemic corticosteroids are the mainstays of therapy. With control of the disease, the corticosteroid dose is gradually reduced to the lowest effective maintenance dose. Too rapid a reduction may result in a rebound flare of the disease. As long-term therapy is often required, institution of alternate-day prednisone together with an immunosuppressive agent have been used. A variety of immunosuppressive agents - such as cyclophosphamide and azathioprine - have been used in an attempt to reduce steroid requirements. Intramuscular gold sodium thiomalate injection has been used with success. However, gold toxicity is a problem. Plasmapheresis (antibody-containing plasma is removed from the blood and replaced with intravenous fluids or donated plasma) may be used in addition to the systemic medications to reduce the amount of antibodies in the bloodstream. Plasma exchange has shown that if may be useful in bringing the disease under control and deserves serious consideration in patients with severe steroid-resistant pemphigus vulgaris. Severe cases of pemphigus are treated similarly to severe burns. Treatment may or may not require hospitalization, including care in a burn unit or intensive care unit. Treatment is aimed at reducing symptoms and preventing complications. Intravenous fluids, electrolytes, and proteins may be required. Mouth ulcers may necessitate intravenous feedings, if severe. Anesthetic mouth lozenges may reduce pain of mild to moderate mouth ulcers. Antibiotics and antifungal medications may be appropriate to control or prevent infections. Systemic therapy as early as possible is required to control pemphigus, but side effects from systemic therapy can be a major complication. Localized treatment of ulcers and blisters may include soothing lotions, wet dressings, or similar measures.

How do I take care of blisters?

Supplies needed?

- Ointment: Antibiotic ointment is a topical antibiotic available here.

- Band-Aids or hypoallergenic paper tape.

- Gauze: Cotton gauze or cotton balls.

- Hydrogen Peroxide: Available at your pharmacy.

Brief routine

- Twice a day: Pour hydrogen peroxide onto the wound or blister.

- Twice a day: Lightly rub the area with a hydrogen peroxide soaked gauze.

- Twice a day: After the peroxide, liberally apply antibiotic ointment with a Q tip.

- Twice a day: If you desire, you may cover with a new bandage.

- It's best to keep the wound continuously moist with Antibiotic Ointment.

- Severe wounds should not be exposed to excessive water.

- While showering, a thick film of antibiotic ointment will prevent water exposure.

- Prevent infection by keeping your fingers off the wound. Please avoid picking.

Expectations (prognosis): If not treated, pemphigus vulgaris is usually fatal within 2 months to 5 years, because of complications. Pemphigus vulgaris can be a life-threatening disease. Untreated, the mortality rate is more than 70%. This figure has declined drastically with the introduction of corticosteroids. It has further decreased with the use of adjutant therapy so that current mortality rates approach 5%. However, the outlook is still more grave in Jewish patients. Most of the patients who die have extensive disease and death is attributable to biochemical abnormalities and secondary infection following immunosuppression. Generalized infection is the most frequent cause of death. Treated, the disorder tends to be chronic in most cases. Side effects of treatment may be severe or disabling. Complications include side effects of systemic medications, secondary bacterial, viral, or fungal infections of the skin, spread of infection through the bloodstream, (sepsis) loss of extensive amounts of body fluids, loss of electrolytes, electrolyte disturbances.

Pemphigus Vegetans