Eczema

UNDERSTANDING

ECZEMA

You

or someone you love may have eczema. But what is eczema? And what can you do about it? How do you control the

itch? Stop the rash? How do you start back on the road to comfort

and recovery? This patient education sheet

was written to help answer questions and concerns like these. Dr. Jacobs wants

to help you understand eczema because, by understanding the disorder, you can

take your first step towards living comfortably within your skin. By the way,

the words “Eczema” and “Dermatitis” mean the same thing. They can be used

interchangeably, and, like “water” and “H2O,” they are synonymous.

What is

Eczema?

A

famous Austrian doctor named Hebra described it well

years ago when he said, "Eczema is

what looks like eczema." Sound confusing? It's not really. What Hebra meant was that

eczema is not defined by what causes, it, but by what it looks like. You see, eczema is really just a general term covering a group of 10 or

12 skin disorders that all look alike, but are caused by different factors. But

interestingly, even though different factors can cause each type of eczema,

there is one common factor that is shared by all types of eczema. That factor

is: Each type of eczema has, in some way, a damaged, dysfunctional, or

perturbed skin barrier. To learn more about the skin barrier, and, when it comes

to eczema, the skin barrier’s role in “keeping the peace,” Please take a few

minutes to read the patient education sheet titled, “Dry Skin and Skin Barrier

Education,” and my booklet, “The ABC’s of Dry and Sensitive Skin.”

Quite

simply, eczema, like a fire, begins when the skin barrier is damaged or

perturbed, allowing the passage of allergens, toxins, and infectious agents

that call forth white blood cells, dryness, and the whole eczematous

inflammatory process that results in what you see and what Hebra descrided as "Eczema is what looks like

eczema."

What Does

Eczema Look Like?

Eczema

has three different stages, each with its own distinctive features. You may experience only the first stage, only

the first and second, or you may go through all three stages. Dermatologists call these three phases of

eczema acute, subacute, and chronic. Acute eczema is

stage number one, starting with some redness, swelling, and itching. The redness quickly changes into blisters

which, when they break, promptly begin oozing or weeping. The itching can become severe at this point,

but you must try hard not to scratch. Scratching only intensifies the itching and worsens your condition.

WHAT TYPES

OF ECZEMA ARE MOST COMMON, AND, WHAT ARE THEY CAUSED BY?

Contact

Eczema or Dermatitis

As

the name "contact" implies, this type of eczema is the result of an

outside irritant making contact with your skin. Contact eczema is usually an allergic reaction. A person only rarely develops a rash after

only one contact. This is the nature of

allergy. The first contact almost never

irritates. It is the second or the third

of fourth or tenth or hundredth contact that irritates. Sometimes the rash develops with the next

encounter, and sometimes it takes years for the skin to suddenly become

sensitive to a certain substance. It

also works the other way what a person reacts to now may, after a few years,

hardly bother him at all he has "outgrown" his allergy. Sometimes the

placement and the shape of the rash can give a clue as to the cause. For example, sensitivity to a certain dye in

shoe leather will affect only the tops and sides of the feet. Or, a rash due to a low shrub could mark the

legs in a horizontal streak. Substances that commonly cause reactions in some

people, or may be causing a reaction in you, are:

- plant (like poison ivy)

- foods (like nuts and shellfish)

- industrial chemicals

- medications applied to the skin

- perfumes

- cosmetics

- fabrics

- household cleaners

- polishing agents

Almost

anything can cause contact dermatitis. A person is never allergic to something

the first time they use it. It takes many repeated exposures before the body

can develop a true allergy to a substance. Often, a person will say, “Dr.

Jacobs, I can’t understand how I can be allergic to my perfume, I have been

using it for 10 years.” Dr. Jacobs explains that the person has used the

perfume for 10 years, and has finally acquired an allergy due to repeated

exposure. The same holds true for allergic reactions to all things. A person

needs to be exposed to a substance repeatedly before an allergy can occur.

Most

of the time, Dr. Jacobs can take a simple history and can find out what you are

allergic to. Sometimes, Dr. Jacobs may have to order blood tests or do special

skin testing to determine your allergies.

Primary

Irritant Eczema or Dermatitis

This

form of eczema is a close cousin of contact dermatitis. The difference lies in the fact that primary

irritant dermatitis is not an allergic reaction the first contact, if it is

long enough and strong enough, will cause eczema to develop in everyone. Examples of substances causing primary

irritant dermatitis are strong acids and alkali (like battery acid and Bleach),

solvents (like turpentine), and strong soaps and detergents.

Atopic

Eczema or Dermatitis

This

type of eczema differs from the fist two that we've just discussed because it

is a hypersensitivity that can be amplified by contact. It is a tendency or disorder that runs in

families and often occurs together with other types of allergic disorders. Infants, for example, who have eczema may

outgrow it by the age of 5 or 6 but often develop asthma or hay fever

later. Atopic eczema is a chronic type

of dermatitis, but acute flare-ups are often triggered by a number of factors,

a few of which are heat, cold, rapid changes in temperature, sudden sweating,

stress, and fatigue.

Eczematous

Dermatitis

An

umbrella title, “eczematous dermatitis” covers any form of eczema not easily

classified into the preceding categories. These eczemas or “dermatitides”

(plural of dermatitis) can be

due to many different factors and appear in many different patterns. For example, infective eczematous dermatitis

is a rash developing in the patch of a draining bacterial, fungal, or viral

infection. In contrast, stasis

dermatitis, a rash stemming from poor circulation due to varicose veins. Stasis

dermatitis usually occurs in swollen legs with poor circulation. Xerotic eczema or nummular eczema occurs in skin that is

chronically dry and inadequately moisturized. Hand eczema may occur from

frequent hand washings or from use of strong solvents at home or work. Eczemas

may occur in a variety of different patterns, and may require different

treatments.

AT

WHAT AGES IS ECZEMA COMMON, AND, WHAT BODY PARTS ARE USUALLY AFFECTED?

Eczema

can occur at any age and on almost any part of the body, with some areas being

more sensitive than others. Contact eczema usually affects the area where

contact was made with an irritating substance. Some good examples are diaper rash in infants, detergent hands in

adults, or a poison ivy reaction in any age group.

WHAT

IS THE TREATMENT FOR ECZEMA?

How

to Care for Sensitive Skin,

Atopic

Skin, Allergic Skin, or Eczematous Skin

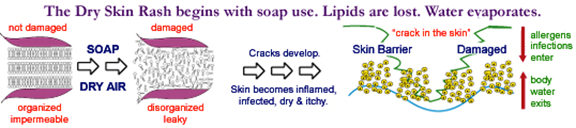

Dry

and sensitive skin problems are among the most common reasons for coming to the

dermatologist. Dry skin is a problem for many people, especially in cool

weather when the air is dry and furnaces are turned on. How does dry skin

develop? Normally, your skin moisture is protected by your skin barrier lipids

filling the intercellular spaces between skin cells. Soap can wash these

protective bio-oils away, and your skin can lose moisture. Dry air further

causes the skin to lose moisture, and your dried skin can scale, flake, and

crack. The tiny cracks in the skin are also called “fissures” and occur within

the lines of the skin. As tiny dry fissures deepen within the skin lines,

inflammation and sometimes infection develops, leading to a medical condition

called: asteatotic or xerotic eczema, the medical names to describe severely dry skin. The words “eczema” or “dermatitis”

are the same and refer to inflamed skin. Eczema or dermatitis can be due to

allergic or irritating substances, infections, low oxygen, drugs, and dryness.

The chapped, cracked “eczematous” areas may become irritated and itchy. The

skin can appear scaled like fish scales, a condition called “icthyosis.” If sensitive skin is a problem, the dry

eczematous skin rash can form patches that resemble ringworm. This condition is

called “nummular” eczema. At times, the skin may peel like parchment paper.

Other times, the skin may appear red and flaky. If low oxygen is a problem as

with swollen or varicose legs, the condition is called “stasis dermatitis.” If

asthma, allergies, or hay fever is in the family history, the dry skin problem

may be magnified. This dry skin condition is called atopic dermatitis. The dry

skin care principles explained in this handout apply to all people who suffer

with dry skin, sensitive skin, allergic or atopic skin, icthyotic skin, nummular skin, or any type of eczema, including stasis.

Moisturization

The

most important part of therapy is to first restore moisture to the skin. It’s

like filling a dry lake bed. Skin lubrication will restore your skin’s

moisture. How is this done? Just add water! Water alone will briefly moisturize

your skin, but the new moisture is soon lost to the air by routine evaporation.

How to prevent evaporation? Creams and ointments provide a protective film or

coating of oil that prevents skin water from evaporating. The oils can also

seep deep into the intercellular spaces and can temporarily refill your skin

barrier so that it can once again function. This protective oil coating

prevents dryness. Any type of oil can prevent water loss. Bath oils can be an

effective way to prevent loss of moisture. You can rub bath oil onto your skin

after a shower or bath. You can add it directly to your bath water: CAUTION:

Slippery tub! When applying bath oil directly to your skin, first, soak in your

tub and wipe your skin with a moist towel. Second, pour a small amount of bath

oil into your hands. Liberally spread it around. Three large tablespoons of

bath oil is enough for the entire body of an average adult male. If you prefer

to use bath oil in the tub, after you have soaked for 10 minutes, add a

tablespoonful of oil to the bath water and soak for 10 to 20 minutes more. Do

not use soap, as you will be cleansed by soaking in the oil-water combination.

After soaking, pat yourself dry with a damp towel. Enough bath oil will remain

on your skin to prevent moisture loss. You can ask your pharmacist to show you

OTC bath oils or mineral oil. If you don’t like bath oil, you can moisturize

with OTC Cetaphil Moisturizing Cream or plain

Vaseline with good results. Sesame oil is also nice. The most important point

to remember: Any skin lubricant is best applied after your skin has been wettened in the bath or shower, so as to trap and hold

moisture in. Think of yourself as a bone dry sponge that has been soaked or

dipped in water. The sponge is then dipped in oil to tightly seal the moisture

in. Here is a recipe for an excellent home made moisturizer: Mix one pound of

Vaseline ointment with sixteen ounces of any fragrance free mineral oil. Add a

small amount of pure water to your liking. Mix them together, well, with an

electric mixer. Apply liberally to your body each day after your bath. You will

find this recipe to be effective and economical.

Treating the

Dry Skin Rash

When

dry skin has developed into an itchy rash, a cortisone cream or ointment

usually brings quick relief. The cortisone may be applied liberally to the rash

and deeply massaged in, usually at bedtime, or after bathing, and one or two

other times during the day. As your rash improves, the cortisone is decreased.

Remember, dry skin requires topical therapy. Many patients would like to treat

their dry skin with either a pill, an injection, or

diet. Some patients have asked if fat intake improves dry skin. Excessive fat

consumption can cause poor health. Please remember, when treating dry skin,

there is no safe substitute for conscientious topical moisturization.

If you want an oral cure, water is the best oral substance to help with dry

skin. Pills aren’t available. Topical care is best. First, soak the water

inside. Second, prevent evaporation with a film of oil.

Soap

Soap

is bad for dry or sensitive skin. Dial, Zest, Lever, Safegaurd,

Ivory, gels, and Irish Spring are among the worst. Soap removes skin oils

needed to hold in moisture. If oils are removed, the skin develops cracks,

fissures, and dry inflammation. Soap should not be used on dry or sensitive

skin. Most of us use far too much soap. Actually, plain water is often just

enough to cleanse the skin. If you can't live without soap, it's OK to use Dove

soap for your face, feet, armpits, and groin.

Avoid

Allergic Items

Sensitive

skin can become itchy when exposed to allergic type substances such as

perfumes, dyes, conditioners, powders, anti-perspirants,

hair sprays, grasses, plants, fragranced products, shampoos, unrinsed laundry detergents, fabric softener sheets, dog or

cat hairs, carpets, chemicals, Aloe Vera, PABA, detergents, acrylic nails,

polishes, nickel, elastic, latex, etc. Hair conditioners can induce itch!

Please avoid perfumes.

Bathing

Persons

with dry skin may bathe

~ or shower once daily:

1.

Use no soap on dry or sensitive skin areas. You may use mild Cetaphil or Aquanil soapless soaps, instead of soap.

2.

After bathing, thoroughly lubricate your skin using one of the methods

described in this educational sheet.

3.

After your bath, you should not towel dry. Wipe off the water with your hands,

then, apply a thin film of moisturizing cream to your entire body. This film

will seal in your new moisture.

4.

For shampoo, use OTC fragrance free DHS Clear Shampoo.

Long-term

Control

Dry

or sensitive skin is usually a long-term problem that may recur often,

especially in winter. When you notice your skin getting dry or itchy, resume

your lubricating routine, proper bathing technique, and avoid soap. If you are

a dry or sensitive skin person, avoid allergic items, especially perfumes and

antibacterial soaps. Aim to restore your protective skin barrier lipids.

What is Dry and Sensitive Skin?

What is dry and sensitive skin? Dry skin is common

problem, especially in cool weather when hot furnaces are turned on and the air

is dry. Young and old, infants and adults, millions of people suffer with dry

and sensitive skin. It may be you or your spouse, your children, your parents,

or even a friend. At highest risk are babies, seniors, diabetics, frequent hand

washers, eczema prone people, atopics, psoriatics, and people on water pills, acne meds, or

wrinkle creams. These people usually suffer with dry and extra sensitive skin.

If you look in the dictionary, there is no good definition

for the term" sensitive skin," but those of you who have it sure know

what it is. Sensitive skin dries out ever so easily, can ignite like a hot

match, and any allergic thing can set it off. If this skin type is neglected

and exposed to soap, dry air, and allergens, simple dry skin can deteriorate

into itchy eczema or the "Dry Skin Rash." Eczema, the Dry Skin Rash,

and most dry and sensitive skin problems can be traced to an easily damaged

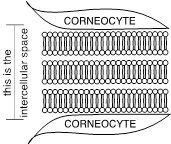

skin barrier located in the upper layers of the skin. Microscopically, the skin

barrier resembles tiny bricks and mortar. Here is a simplified diagram of the

human skin barrier.

If you are a dry and sensitive person and you neglect your

skin barrier, you will have problems forever. The truth is, your skin barrier

needs daily care, but ironically, most dry and sensitive people are unaware of

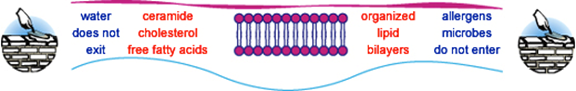

their skin barrier organ. A well-tuned skin barrier will keep body water inside

and will prevent allergens and microbes from entering your body. The

"bricks" are the corneocyte skin cells. The

"mortar," situated between skin cells, is made of three lipid-oils:

Free fatty acids, ceramide, and cholesterol. For

normal skin barrier functioning to occur, the three lipids must be

"organized" into precise layers called "lipid bilayers."

Here is an example of well organized, healthy, skin

barrier lipids:

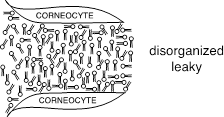

Here is an example of disorganized, unhealthy, skin

barrier lipids:

How Do You Get Dry Skin?

If cholesterol, ceramide, and

free fatty acids are stripped away as with excessive soap use, the lipid

bilayers will break down and the skin barrier is damaged.

In this depleted state, the skin barrier will leak, and

thus, water will evaporate, allergens will penetrate, and microbes can enter to

infect. The skin becomes dry, inflamed, and infected. A rash ensues: The Dry

Skin Rash. Help! Some people try calamine, but dry calamine does nothing for

dry skin. Some people head to the shower and scrub their bodies with soap. This

only adds fuel to the fire. Hoping for relief, some splash rubbing alcohol all

over their lipid-depleted body.

They don't realize that soap and alcohol are only

stripping more lipids and causing more skin barrier damage. Finally, the dry

person goes to a local urgent care and gets cortisone pills. But, cortisone is

only a short-term fix for a long-term skin problem. What this suffering dry and

sensitive soul really needs is the ABC Skin Care.

|

||||||||||